The Internet Freedom Festival 2017 (Tuesday)

Day two of the Internet Freedom Festival was intense.

Rapid Response To Targeted Threats

It started out with a session by Civil Society Centre for Digital resilience (CiviCDr) and ASL19 on rapid response, which I now understand means helping people in the aftermath of a hacking attack. In this particular case it was about human rights workers having their email accounts hacked by Iranian state sponsored hackers.

As far as I can tell, CiviCDR connects human rights organisations with digital trainers and experts, facilitating these services:

- “baseline” training: getting a group of connected organisations up to a basic level of digital security (two-factor auth, etc)

- incident response: connecting victims of attack with people who can investigate

- notifications: emailing the community when new types of attack are discovered

My main learnings from this session:

- Iran performs very sophisticated, one-off attacks tailored for an individual.

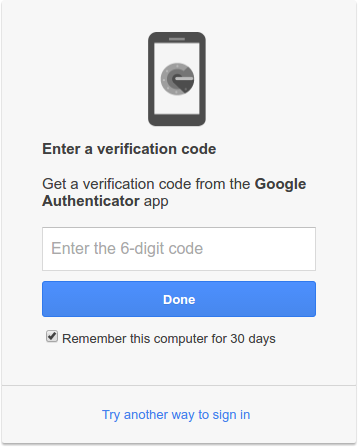

- Google Authenticator 2-factor codes can only be used once to login once, whereas SMS-based codes are valid for 30 minutes and can be used multiple times.

- There have been successful social-engineering attacks on SMS-based two-factor authentication.

- Many human rights organisations use Wordpress, but don’t know to keep it updated, so get attacked this way.

Two-factor authentication hugely improves security, but a determined targeted attack can still trick users.

There was a bit of discussion about scaling this with automation, and I heard about a tool called HSF Reporter, which simplifies reporting suspicious emails to the Harms Stories Framework (HSF) engine (can’t find a link).

Journalism and the Right to be Forgotten

This session highlighted the harm to journalism caused by the so called “right to be forgotten”. That doesn’t refer to just one thing, although the European court’s decision that Google had to process right to be forgotten requests is a well-known example.

We learned that “reputation management” firms charge wealthy clients $50,000+ to “clean” their online reputation, serving scary-sounding take-down requests to news sites and blogs which write about their client in a potentially negative light. Small organisations don’t always understand the law, and don’t find it worth going to court, so simply comply with such requests.

Such cases are clearly harmful for public interest reporting.

There are other cases (which these laws were presumably designed for), which make complete sense to me - for example, purging past misdemeanors that are no longer relevant to the public interest.

My take-away from this session was that governments are scrambling to implement laws, these laws overlap with existing data protection and libel laws, and that jurisdictions and borders just make things worse in an Internet world.

Interesting: the BBC maintains a list of sites which have been delisted from Google. The Guardian disapproves. Take a look at five random articles there and you’ll see the problem.

What a mess.

How activists, western media, and USBs and SD cards are revolutionizing North Korean society

Wow. This deeply moving session, painstakingly and carefully told through an interpreter and partner, told of Jung Gwang Il’s false imprisonment, torture and ultimate escape from North Korea.

No Chain, his human-rights NGO, is exposing North Koreans to the outside world by smuggling in USB sticks, SD cards and other devices with a variety of sneaky methods.

He sees times changing in North Korea, with small acts of civil disobedience that were “unthinkable” five years ago.

The main reason for attending the IFF was to call for help. North Korea really has no Internet, so Internet Freedom just doesn’t apply there. He asked for creative ways of bringing Internet to the country, being mindful that doing so is illegal.

Censorship Resistant Circumvention Tool Delivery

In this session I learned about Paskoocheh, another ASL19 project for delivering Android apps to censored users in Iran.

In Iran, the Google Play store doesn’t list “circumvention” apps such as VPNs, and other types of app deemed unsuitable by the government.

Paskoocheh uses some cool delivery techniques like an email autoresponder and a Telegram bot.

To avoid blocking by state censors, it takes advantage of the popularity of S3, hosting files at https://s3.amazonaws.com/....

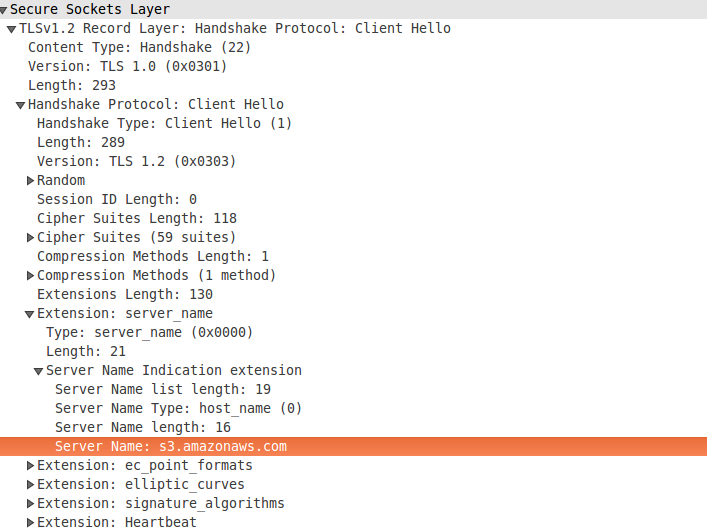

A censor needs to look inside the packet to be choose whether to block it. In this case, all they could see would be the domain part of the request (the Server Name Indication extension to the TLS handshake), not the URL path.

On the wire, all requests to URLs under s3.amazonaws.com look the same…

That makes it hard to know whether the request is for an app, or for one of millions of other S3 resources on the Internet.

That certainly doesn’t make it unblockable but it’s working at the moment.

This was a really impressive project, especially considering it’s been going for under a year.