Hack the Hive: Connecting a Beehive to the Internet

*One of my resolutions for 2016 was to make an effort to write up my “hack days”

- the 20% time I’ve been trying out for the last six months. Although I don’t think I’ve wasted that time, I’ve hacked on a lot of different stuff but don’t have much to show for it. I think it’ll be great to be able to refer back to each day with a blog post.*

Why We’re Hacking a Hive

My friend Hannah works at Ykids, a charity in Bootle who run activities and things for kids. One of the groups are budding young beekeepers and they have a couple of active beehives. The kids are amazing: they’re totally into their beekeeping.

A while back Hannah and I were chatting about whether we could monitor the hives remotely. There are a load of reasons to do this, but one in particular is checking if the inside of the hive has got too cold. In the winter the bees form a tight ball and buzz around to generate heat, but it’s possible that they can get too cold and die. If you can monitor the temperature of the hive, you can intervene and add extra insulation. We decided to do a Minimum Viable Hive by monitoring the temperature and logging it remotely somewhere. This is a techie write-up of the electronicsy bits.

Hera 200 is an Arduino Leonardo + GSM

The Hera 200 is a sweet little board with effectively an Arduino Leonardo, a GSM shield, a battery, some neat power electronics and a tough little case. My friend Adrian put me onto this as he’s used it in another project, powered by a low cost 12V leisure solar panel. The plan is to use this to take temperature measurements and upload them using mobile data to somewhere on the Internet.

Temperature Sensing with a DHT22

We used a temperature and humidity sensor called the DHT22 which is pre-calibrated, meaning it has a little chip onboard with a lookup table to ensure you get calibrated readings. Helpfully, Adafruit released a free software library to read these devices. Although the tutorial website was down when I looked at it, the library was so clear that I was able to get going easily: it just worked (for once).

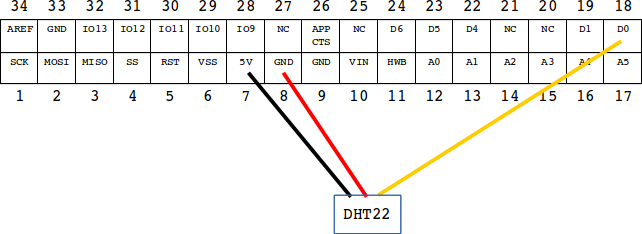

The DHT22 sensor is connected to three pins on the Hera 200’s output connector. Thankfully I had the schematic to work out which pin mapped to which Arduino pin. The diagram below shows the connections:

Arduino in Low Power Mode

The Arduino code simply wakes up every 10 minutes, activates the GSM modem, sends the temperature and humidity sensors to a remote server then goes back to sleep. It uses the Low Power library to put the Arduino into a very low power sleep mode between cycles.

All the Arduino code is on GitHub.

Data Forwarding Server

I decided the Arduino should send data directly to a tiny server that I control rather than uploading it to a third-party. The reason for this is that I’m wary of third party servers coming and going, or changing the way their API works. Once the Arduino is deployed in a field it will be awkward to update. It’s much simpler to re-deploy a tiny Python app running on a server on the Internet.

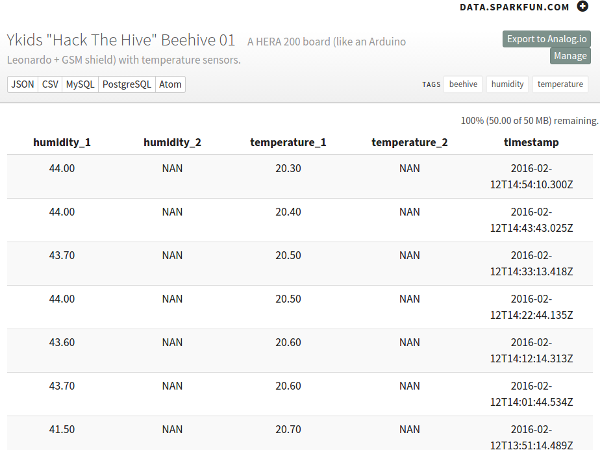

Note that NAN entries due to a missing sensor!

The server code forwards on to Sparkfun which lets you download the data in various formats.

With this setup, there’s nothing stopping us forward the data on to multiple places, for example I’d like to try out opensensors.io.

The server code is on Github.

Watch this Space!

We’re building the hive on Monday, and it’ll be up to the kids to work out how to install the sensors, mount the solar panel and keep everything waterproof.

I’ll make sure I post some photos, probably in another blog.

Visit our Github organisation or look at the data.